- What’s hiding underneath solar panels?

- NREL research on solar–pollinator habitats highlights how prairie restoration under solar panels supports pollinators, protects soil, and enhances biodiversity.

- Could this practice shape the future of sustainable energy and ecological conservation?

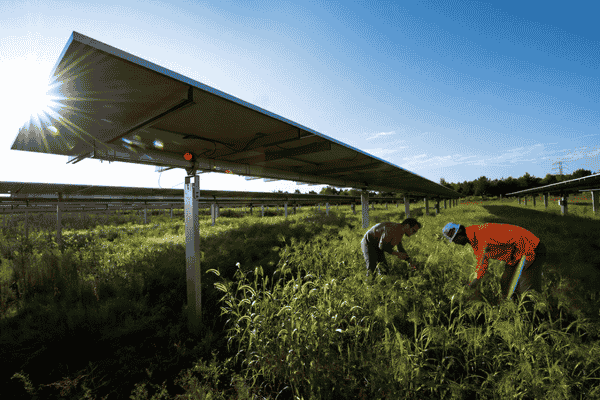

The growth in utility-scale solar development is leading to questions about how best to use the land underneath solar panels and what impacts solar installations have on soil and habitat. An increasingly common practice is to establish habitat beneath and around solar modules that is beneficial to biodiversity and the local ecosystem.

In a series of studies undertaken by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Argonne National Laboratory, research partners from the University of Minnesota and Temple University, and practitioners from MNL (formerly Minnesota Native Landscapes)—researchers take a deep look at the interactions between habitat, pollinators, and solar energy production on three large working solar farms in Minnesota.

These solar–pollinator sites are the first U.S. commercial utility-scale photovoltaic (PV) solar projects that included comprehensive research on ecovoltaics.

Ecovoltaics—colocating PV and ecologically-beneficial planting practices—is related to agrivoltaics through the innovative dual use of land under solar projects. Agrivoltaics focuses specifically on agricultural production, whereas ecovoltaics focuses on soil improvement, provision of ecosystem services, and other factors that could benefit agriculture and ecosystems.

Findings from these studies show that it is possible to establish native prairie under solar panels and, by doing so, provide soil benefits and habitat for wildlife and pollinators.

Solar sites can restore prairie and host diverse ecological activity

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) is transforming energy through research, development, commercialization, and deployment of renewable energy and energy efficiency technologies.

For six years, NREL’s Innovative Solar Practices Integrated with Rural Economies and Ecosystems (InSPIRE) team has been researching the combined potential impacts of solar development on native vegetation, pollinators, PV performance, and soil. Prior research has addressed only one aspect of these interactions at a time. This study is the longest-run, most comprehensive assessment of interactions between PV, soil, habitat, and pollinators.

The findings are presented in a series of scientific journal articles about maintaining native vegetation under solar panels (in Earth’s Future), insect community responses to habitat establishment (in Environmental Research Letters), and native seed mix impacts on pollinator habitats (in Environmental Research Communications).

The Minnesota pollinator sites, which are owned by Enel Green Power, won a North American Agrivoltaics Award (NAAA) this year: Learn more about the Atwater and Eastwood solar sites on the NAAA website.

These are the main environmental benefits established over the course of this research, to date:

- Prairie restoration activities can occur underneath solar panels.

- When prairie is established, pollinators will use the site as much as dedicated conservation land, evidenced through an increased abundance and diversity in both vegetation and pollinators.

- Planting pollinator habitat and native vegetation can mitigate some of the environmental damage done to the soil and habitat when solar installations are built.

Benefits of ecovoltaics vary across climates and geographies

In terms of impacts on PV modules, researchers found that even though native habitat decreased PV module temperatures compared to bare ground, which is generally good for solar panels, it did not seem to increase electricity production. Instead, researchers observed little to no impact to annual generation. This finding is counter to studies in other regions that have shown increases in electricity production, which suggests that microclimatic interaction between PV arrays, soil, and vegetation is not consistent across varying landscapes and climates.

Site assessment is crucial for determining these relationships and the potential benefits or impacts.

“One of the most important results from this research is that we need to study more sites,” NREL agrivoltaics researcher Chong Seok Choi said. “For instance, site-specific climate—how much moisture is in the air, for example—can affect whether the cooling we observe from native habitat can lead to increased PV efficiency. There’s still so much work to be done.”

Findings from these studies underline the value of long-term research. For example, researchers found that having native habitat under solar panels can protect soil from future erosion but also that it takes a long time to restore soil after damage from intensive corn and soy production. The overall impact of soil restoration activities at these sites will not be clear for years to come. They also found that it took three to four years after PV construction for prairie vegetation to fully establish, and certain species did not appear until years five and six. “As a relatively new land management practice, there are several information gaps and considerations associated with solar-pollinator habitat that need to be addressed,” said James McCall, NREL agrivoltaics researcher.

A promising aspect of this research is that, with growth in pollinator activity, solar–pollinator habitat can help improve crop production in nearby farms and fields, as findings (published in 2018 in Environmental Science & Technology) suggest.

“One key takeaway from this research is that relationships between soil health, native pollinator habitat, insect abundance, and PV production can vary from site to site. Additional studies at more sites will be critical to build the foundation needed to apply generalized findings across a wide variety of geographies and time frames,” McCall said.

“We plan to continue research at the site and to see how the vegetation persists over time,” he said. “We’re just starting to see certain vegetation species emerge, and studying how these benefits may change or continue over the life of the solar project is important for continued deployment of ecovoltaic projects.”

This article has been adapted from source material published by National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), and Argonne National Laboratory researchers.

Comments