Any resident of the Great Plains can attest to the massive scale of wind farms that increasingly dot the countryside. In the Midwest and elsewhere, wind energy accounts for an ever-bigger slice of U.S. energy production: In the past decade, $143 billion was invested into new wind projects, according to the American Wind Energy Association.

However, the boom in wind energy faces a hurdle — how to effectively and cheaply store energy generated by turbines when the wind is blowing, but energy requirements are low.

“We get a lot of wind at night, more than at daytime, but demand for electricity is lower at night, so, they’re dumping it or they lock up turbines — we’re wasting electricity,” said Trung Van Nguyen, professor of petroleum & chemical engineering at the University of Kansas. “If we could store this excess at night and sell or deliver it during daytime at peak demand, this would allow wind farm owners to make more money and leverage their investment. At the same time, you deploy more wind energy and reduce demand for fossil fuels.”

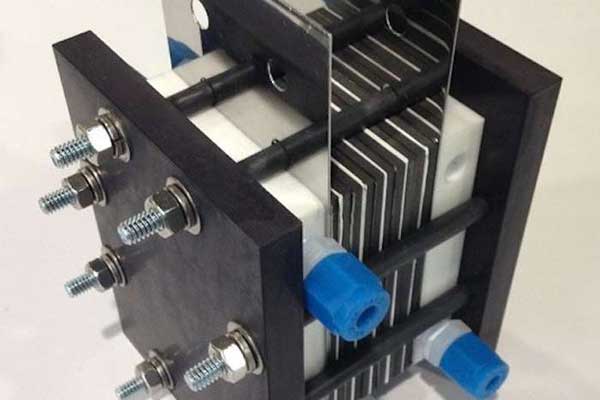

Since 2010, Nguyen has headed research to develop an advanced hydrogen-bromine flow battery, an advanced industrial-scale battery design — it would be roughly the size of a semi-truck — that engineers have strived to develop since the 1960s. It could work just as well to store electricity from solar farms, to be discharged overnight when there’s no sun.

Funded first by the National Science Foundation and later by the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, Nguyen has worked with researchers from the University of California at Santa Barbara, Vanderbilt University, the University of Texas at Arlington and Case Western Reserve University. Along the way, Nguyen has overseen breakthrough work on key components of hydrogen-bromine battery design.

For one, there’s the electrode Nguyen developed at KU. A battery’s electrode is where the electrical current enters or leaves the battery when it’s discharged. To be maximally efficient, an electrode needs a lot of surface area. Nguyen’s team has developed a higher-surface-area carbon electrode by growing carbon nanotubes directly on the carbon fibers of a porous electrode.

“Before our work, people used paper-carbon electrodes and had to stack electrodes together to generate high-power output,” he said. “The electrodes had to be a lot thicker and more expensive because you had to use multiples layers — they were bulkier and more resistive. We came up with a simple but novel idea to grow tiny carbon nanotubes directly on top of carbon fibers inside of electrodes — like tiny hairs — and we boosted the surface area by 50-70 times. We solved the high-surface requirement for hydrogen-bromine battery electrodes.”

A key issue remaining before a hydrogen-bromide battery can be marketed successfully is the development of an effective catalyst to accelerate the reactions on the hydrogen side of the battery and provide higher output while surviving the extreme corrosiveness in the system. Now, with funding from an NSF sub-award through a private company called Proton OnSite, Nguyen is verging on solving this last barrier.

“I think we’re on the verge of a real breakthrough,” he said. “We need a durable catalyst, something that has the same activity as the best catalyst out there, but that can survive this environment. Our previous material didn’t have sufficient surface area to give enough power output. But I’ve been able to continue to work on this rhodium sulfide catalyst. I think we’ve figured out a way to increase surface area. We now have a better way, and we may publish that in three to six months — we have some minor issues to resolve, but I think we’ll have a suitable material for the hydrogen reaction in this system.”

The new results to develop an industrial scale advanced hydrogen-bromine flow battery will be presented at the meeting of the Electrochemical Society in Seattle this May.

Indeed, Nguyen — who has founded several startup companies over his research career — noted the new hydrogen-bromine battery soon could be commercialized, and easily could be scaled to MW (power) MWh (energy) scales, coming in modular container form, about 1MWh in a full-size container. But he cautioned it could only be used in remote, industrial sites — places like wind and solar farms, where the huge batteries likely would be buried underground.

“This energy storage system, because of its corrosiveness, isn’t suitable for residential or commercial systems,” he said. “Bromine is like chlorine gas. Dig a hole, line it with cement or plastic, drop this battery down and cover it up — it should be in an enclosed or sealed system to prevent leakage or emission of bromine gas. This will be suitable only for large-scale remote energy storage like solar farms and wind farms.”

The KU researcher said the rise of renewable energy would depend on technology breakthroughs that make the economics attractive to energy producers and investors, and he hoped his new battery design could play a part.

“The way we use fossil fuel for energy is very inefficient, wasteful and generates greenhouse gasses,” Nguyen said. “For fossil fuels, you make the initial investment, and also you pay for operation every day — pay for coal or for natural gas for rest of the life of the power plant. Once you make the initial investment in renewable, the electricity you make is free.”

Comments