Solar cells convert light into electricity. While the sun is one source of light, the burning of natural resources like oil and natural gas can also be harnessed.

However, solar cells do not convert all light to power equally, which has inspired a joint industry-academia effort to develop a potentially game-changing solution.

“Current solar cells are not good at converting visible light to electrical power. The best efficiency is only around 20%,” explains Kyoto University’s Takashi Asano, who uses optical technologies to improve energy production.

Higher temperatures emit light at shorter wavelengths, which is why the flame of a gas burner will shift from red to blue as the heat increases. The higher heat offers more energy, making short wavelengths an important target in the design of solar cells.

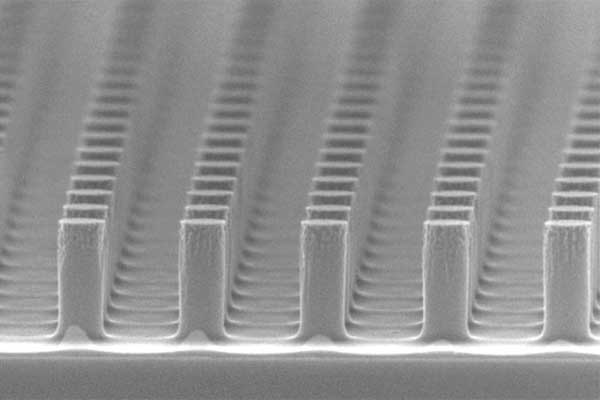

Using nanotech to boost solar output: A Kyoto University and Osaka Gas silicon device could double the energy conversion rate of solar cells. Each vertical rod measures about 500 nm in height. Credit: Kyoto University/Noda Lab

“The problem,” continues Asano, “is that heat dissipates light of all wavelengths, but a solar cell will only work in a narrow range.

“To solve this, we built a new nano-sized semiconductor that narrows the wavelength bandwidth to concentrate the energy.”

Previously, Asano and colleagues of the Susumu Noda lab had taken a different approach. “Our first device worked at high wavelengths, but to narrow output for visible light required a new strategy, which is why we shifted to intrinsic silicon in this current collaboration with Osaka Gas,” says Asano.

To emit visible wavelengths, a temperature of 1000˚C was needed, but conveniently silicon has a melting temperature of over 1400˚C. The scientists etched silicon plates to have a large number of identical and equidistantly-spaced rods, the height, radii, and spacing of which was optimized for the target bandwidth.

According to Asano, “the cylinders determined the emissivity,” describing the wavelengths emitted by the heated device.

Using this material, the team has shown in Science Advances that their nanoscale semiconductor raises the energy conversion rate of solar cells to at least 40%.

“Our technology has two important benefits,” adds lab head Noda. “First is energy efficiency: we can convert heat into electricity much more efficiently than before. Secondly is design. We can now create much smaller and more robust transducers, which will be beneficial in a wide range of applications.”

Reference(s):

Publication: Takashi Asano, Masahiro Suemitsu, Kohei Hashimoto, Menaka De Zoysa, Tatsuya Shibahara, Tatsunori Tsutsumi, Susumu Noda. Near-infrared–to–visible highly selective thermal emitters based on an intrinsic semiconductor. Science Advances, 2016

Research story: Kyoto University | January 17, 2017 (source)

Comments