Solar is now the cheapest form of energy on the planet and has been the fastest globally-growing energy resource for 18 consecutive years.

Despite its recent success, however, this hasn’t always been the case. Flashback three-quarters of a century, and solar had yet to be commercialized, with costs so high that only the most advanced institutions could develop it. So, how, then, did solar transform from a niche and cost-prohibitive technology into the emerging backbone of the renewable energy economy?

The introduction of the silicon solar cell

Contemporary solar innovation originated in 1950’s New Jersey, United States (US). Researchers at then-known Bell Telephone Laboratories, an industrial research hub founded by Alexander Graham Bell, designed and manufactured the first modern silicon solar cell, achieving an efficiency of approximately 6%.

An extremely impressive feat at the time, Bell Telephone Laboratories would set the stage for solar R&D for years.

A response to OPEC’s oil embargo

Fast forward to the 1970s oil crisis, and alternative energy sources were back in the limelight.

Recognizing the threat posed by an overreliance on energy imports, President Richard Nixon launched Project Independence in 1973, seeking to wean the US economy off foreign oil by investing in energy efficiency and domestic nuclear and coal assets.

Four years later, Democratic President Jimmy Carter took control of the White House with a revised approach to energy independence.

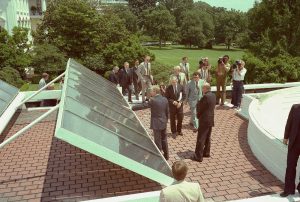

Unlike the previous administration, Carter incentivized renewable energy development — particularly solar — through generous tax incentives and R&D funding. Additionally, Carter’s famous white-house solar panels were installed, which had the added benefit of raising public awareness for solar technology.

White House Solar Panels with Jimmy Carter. (Canadian Centre for Architecture)

Carter’s reorientation of Project Independence was strongly influenced by Paul Maycock, a scientist and later Photovoltaics Chief for the first Department of Energy (which Carter developed).

Maycock theorized an inverse relationship between solar development and cost and encouraged a quick buildout of the sector — with necessary public subsidization — to achieve rapid cost reductions. Before Carter’s administration could truly put Maycock’s theory to the test, however, President Ronald Reagan assumed control of the presidency and ended American leadership in solar technology… at least for the time being.

The start of the modern solar industry

For the next two decades, solar cells would continue to make modest strides, particularly due to Japan’s embrace of solar incentives in the 1990s.

It took until German policymakers introduced an ambitious feed-in-tariff policy in 2000, however, for the global solar industry to hit its stride truly. Under this program, Germany offered power companies that produced renewable energy generous, 20-year contracts at twice the market rate, massively expanding the solar industry’s domestic profitability.

Germany’s private sector responded with utility-scale deployments, drastically increasing solar energy’s penetration in Europe’s largest market.

Chinese solar manufacturer Suntech — one of the earliest of its kind — sought to capitalize on Germany’s rapidly growing FIT market by exporting solar panels and quickly found massive success.

Seeking their own opportunities, additional Chinese solar factories began popping up, and within just a few years, production had hit new highs and prices had new lows. It was clear by this point that Maycock’s initial hypothesis was correct.

Solar fever goes global

By demonstrating how solar could benefit from economies of scale, Germany and China’s cross-national collaboration attracted the attention of global policymakers, which soon began introducing their own incentives to spur solar growth.

In the U.S., both homeowners and businesses qualify for a federal tax credit equal to 26 percent of the cost of their solar panel system minus any cash rebates. The timeline for the eventual end of the ITC is in 2022.

Importantly, the United States was among the nations to do so, passing the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which included an investment tax credit of up to 30% for solar deployments. By enabling companies to lease out solar panels while claiming the federal government’s tax credits, an entirely new market opened up for solar providers, with companies like Sunrun — which was founded in 2007 — emerging as a result.

Over the next few years, various nations, including France, Spain, China, Mexico, and the Czech Republic, among many others, adopted policies to bolster their solar markets. Most importantly, to drive down costs, China launched a feed-in-tariff initiative in 2009 — based on Germany’s wildly successful model.

The Golden Sun Program, as it was dubbed, dwarfed China’s previous solar industry subsidies and catalyzed the nation’s industrial photovoltaic dominance. Within just a few years, China became the largest solar technology manufacturer and solar electricity producer, which has remained the case.

And in 2020, the International Energy Agency named solar the most affordable energy source on the planet.

Lessons for the future of the clean economy

In a remarkably brief window, solar energy transformed from an experimental technology with only small-scale market applications into a pinnacle of the global energy system.

This has been no accident. It’s taken years of publicly-backed innovation, heavy subsidization, and global collaboration and information sharing for solar energy to reach this point. But out of this process, important lessons have presented themselves that can aid today’s energy transition.

Most importantly, political leadership is needed to help emergent technologies overcome existing and entrenched market systems, which tend to be self-reinforcing. Without government support, the private sector has no safety or incentive to explore costly but potentially revolutionary technologies — which can greatly reduce overall innovation.

Leveraging the extensive resources of the public sphere and the expertise and R&D capacity of the private sector is the most efficient manner through which new technologies can be commercialized. But it takes time. And every disruption along the innovation process — like eliminating subsidies — sets back the clock.

Policymakers should be cognizant of this as they look to replicate the solar industry’s development pathway with other technologies, be it battery storage, electric vehicles, or heat pumps.

Solar energy has given the world a guidebook to making sustainable technologies profitable and highly effective — as best we can, we should follow it.

Comments