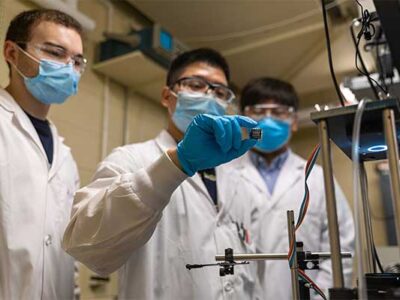

Scientists at the Energy Department’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) are studying what may seem paradoxical – certain defects in silicon solar cells may actually improve their performance.

The findings run counter to conventional wisdom, according to Pauls Stradins, the principal scientist and a project leader of the silicon photovoltaics group at NREL.

Deep-level defects frequently hamper the efficiency of solar cells, but NREL theoretical research suggests that defects with properly engineered energy levels can improve carrier collection out of the cell, or improve surface passivation of the absorber layer.

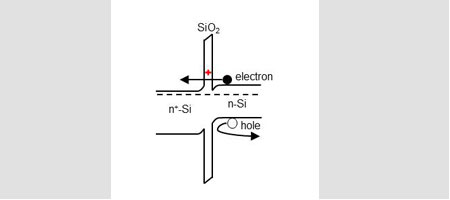

Researchers at NREL ran simulations to add impurities to layers adjacent to the silicon wafer in a solar cell. Namely, they introduced defects within a thin tunneling silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer that forms part of “passivated contact” for carrier collection, and within the aluminum oxide (Al2O3) surface passivation layer next to the silicon (Si) cell wafer. In both cases, specific defects were identified to be beneficial.

The simulations were accomplished using NREL’s supercomputer and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center.

The research by Stradins, Yuanyue Liu, Su-Huai Wei, Hui-Xiong Deng, and Junwei Luo, “Suppress carrier recombination by introducing defects: The case of Si solar cell,” appears in Applied Physics Letters.

Finding the right defect was key to the process. To promote carrier collection through the tunneling SiO2 layer, the defects need to have energy levels outside the Si bandgap but close to one of the band edges in order to selectively collect one type of photocarrier and block the other. In contrast, for surface passivation of Si by Al2O3, without carrier collection, a beneficial defect is deep below the valence band of silicon and holds a permanent negative charge. The simulations removed certain atoms from the oxide layers adjacent to the Si wafer, and replaced them with an atom from a different element, thereby creating a “defect.” For example, when an oxygen atom was replaced by a fluorine atom it resulted in a defect that could possibly promote electron collection while blocking holes.

The defects were then sorted according to their energy level and charge state. More research is needed in order to determine which defects would produce the best results. The principles used in this study are applicable to other materials and devices, such as photoanodes and two-dimensional semiconductors. A recent study by the same authors has shown that the addition of oxygen could improve the performance of those semiconductors. For solar cells and photoanodes, engineered defects could possibly allow thicker, more robust carrier-selective tunneling transport layers or corrosion protection layers that might be easier to fabricate.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy SunShot Initiative as part of a joint project of Georgia Institute of Technology, Fraunhofer ISE, and NREL, with a goal to develop a record efficiency silicon solar cell.

The SunShot Initiative is a collaborative national effort that aggressively drives innovation to make solar energy fully cost-competitive with traditional energy sources before the end of the decade. Through SunShot, DOE supports efforts by private companies, universities, and national laboratories to drive down the cost of solar electricity to $0.06 per kilowatt-hour. Learn more at energy.gov/sunshot.

NREL is the U.S. Department of Energy’s primary national laboratory for renewable energy and energy efficiency research and development. NREL is operated for the Energy Department by The Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC.Scientists at the Energy Department’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) are studying what may seem paradoxical – certain defects in silicon solar cells may actually improve their performance.

The findings run counter to conventional wisdom, according to Pauls Stradins, the principal scientist and a project leader of the silicon photovoltaics group at NREL.

Deep-level defects frequently hamper the efficiency of solar cells, but NREL theoretical research suggests that defects with properly engineered energy levels can improve carrier collection out of the cell, or improve surface passivation of the absorber layer. Researchers at NREL ran simulations to add impurities to layers adjacent to the silicon wafer in a solar cell. Namely, they introduced defects within a thin tunneling silicon dioxide (SiO2) layer that forms part of “passivated contact” for carrier collection, and within the aluminum oxide (Al2O3) surface passivation layer next to the silicon (Si) cell wafer. In both cases, specific defects were identified to be beneficial.

The simulations were accomplished using NREL’s supercomputer and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center.

The research by Stradins, Yuanyue Liu, Su-Huai Wei, Hui-Xiong Deng, and Junwei Luo, “Suppress carrier recombination by introducing defects: The case of Si solar cell,” appears in Applied Physics Letters.

Finding the right defect was key to the process. To promote carrier collection through the tunneling SiO2 layer, the defects need to have energy levels outside the Si bandgap but close to one of the band edges in order to selectively collect one type of photocarrier and block the other. In contrast, for surface passivation of Si by Al2O3, without carrier collection, a beneficial defect is deep below the valence band of silicon and holds a permanent negative charge. The simulations removed certain atoms from the oxide layers adjacent to the Si wafer, and replaced them with an atom from a different element, thereby creating a “defect.” For example, when an oxygen atom was replaced by a fluorine atom it resulted in a defect that could possibly promote electron collection while blocking holes.

The defects were then sorted according to their energy level and charge state. More research is needed in order to determine which defects would produce the best results. The principles used in this study are applicable to other materials and devices, such as photoanodes and two-dimensional semiconductors. A recent study by the same authors has shown that the addition of oxygen could improve the performance of those semiconductors. For solar cells and photoanodes, engineered defects could possibly allow thicker, more robust carrier-selective tunneling transport layers or corrosion protection layers that might be easier to fabricate.

This article has been published here by the PVBuzz Media team from the original news release from NREL.

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy SunShot Initiative as part of a joint project of Georgia Institute of Technology, Fraunhofer ISE, and NREL, with a goal to develop a record efficiency silicon solar cell.

The SunShot Initiative is a collaborative national effort that aggressively drives innovation to make solar energy fully cost-competitive with traditional energy sources before the end of the decade. Through SunShot, DOE supports efforts by private companies, universities, and national laboratories to drive down the cost of solar electricity to $0.06 per kilowatt-hour.

NREL is the U.S. Department of Energy’s primary national laboratory for renewable energy and energy efficiency research and development. NREL is operated for the Energy Department by The Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC.

Comments